During a short period between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th Gibraltar was blessed - at least for some people - with the establishment of several more or less enduring institutions. Over the next hundred years or so they attained reputations which went far beyond those that they were actually entitled to.

Nevertheless the ones that have survived are still looked upon by the majority of the local population with considerable pride and affection - despite the fact that it was only very recently that non-British civilian residents were allowed to participate in any of them.

Nevertheless the ones that have survived are still looked upon by the majority of the local population with considerable pride and affection - despite the fact that it was only very recently that non-British civilian residents were allowed to participate in any of them.

One of these institutions was the Garrison Library, the brainchild of the son of a naval surgeon, John Drinkwater (see LINK) who joined the Royal Manchester Volunteers as an ensign in 1777 at the age of fifteen. When he enlisted he thought he would be sent to America as General Burgoyne had just surrendered his army at Saratoga. As fate would have it Drinkwater’s regiment was almost immediately posted to Gibraltar.

John Drinkwater

There he survived the Great Siege with all its attendant life-threatening risks and inconveniences. When it was all over he was ordered home and disbanded. Not long afterwards in 1785 he published his famous account - A History of the Siege of Gibraltar.

Despite the fact that it was based on what must have been a teenager’s diary, it quickly established its reputation as a military classic. Written in the style of a much older man one gets the impression that he was not just a good soldier but also something of an intellectual. For Drinkwater, not having had enough to eat during the Siege may have been bad enough, but not having had enough to read must have been torture.

When Drinkwater returned to the Rock after purchasing a company in the Royal Regiment of Foot he discovered that Gibraltar was even less of a literary haven in peace time than it had been when at war. In 1795 he decided that some sort of remedy was required. He convinced several of his fellow officers to donate some of their books and together with money raised through subscription he rented some rooms near the Convent and founded the Garrison Library.

The clincher came when it became apparent that the Governor himself - Sir Robert Boyd - thoroughly approved of the idea and started off the subscription with a personal contribution of £100 - an extremely generous contribution in those days.

A few years later it became quite clear that the place was inadequate and plans were made to build new premises. The Commander in Chief of the British Army, The Duke of York, got to hear of this and – as such matters were dealt with at the time – had a private chat with the Prime Minister, Pitt the Younger, who amiably agreed to have the British Government foot the bill. No doubt the whole thing was settled at one of the Pall Mall clubs that both of these gentlemen happened to be frequenting at the time.

Letter from O'Hara to the Duke of York

The Duke of York's reply

Pitt the Younger

The construction work began in 1800. According to E.R Kenyon in his Gibraltar under Moor, Spaniard and Briton, (see LINK) it was built on land identified on a 1745 map as “commonly called the Governor’s Garden” and on another of 1743 as “Inhabitant’s Garden”. I am not sure what map he was referring to but the one produced by the Chief engineer in the mid 18th century makes it hard to decide exactly which plot of land was used. To boot, Governor’s Parade was known as French Parade at the time.

The new premises were handsomely designed by Colonel William Fyers (see LINK) who also became its first Librarian, a post he was happy to take on in conjunction with his real day job of Chief Engineer of Gibraltar. The library seems to have incorporated a printing service almost from the start as the Standing Orders of 1802 were printed by the Garrison Library Printing Office - not exactly the bible but certainly the first book ever printed in Gibraltar.

Colonel William Fyers (John Hoppner)

I have to say that Drinkwater was exceedingly lucky with his Governor’s. If he had tried his luck with Charles Rainsford he would surely have failed. He had once been secretary to James O’Hara’s, Earl Tyrawley. Rainsford ruled the roost from 1794 to 1795 when he was succeeded by Charles O’Hara who happened to be Tyrawley’s son.

According to Sarah Fyers - daughter of Colonel William Fyers and known within British circles as ‘the Beauty of the Rock’ - Rainsford was an absolute odd-ball.

He was she wrote:

. . . a most eccentric man and a firm believer in animal magnetism.

Apparently he always kept an empty chair for his dead wife, whom he believed periodically visited him through the convent window. He was also well known for an interest in alchemy.

The new library, a stone-built Regency style building with rather pleasant surrounding gardens was imposing by local standards. It was officially opened in 1804 by the Governor who succeeded O’Hara - Prince Edward the Duke of Kent - Queen Victoria’s father. A marble tablet with the following inscription was placed in the centre of the facade:

GIBRALTAR GARRISON LIBRARY,

Erected by command of his Majesty,

KING KING GEORGE THE THIRD.

Commenced, A. D. 1800,

Under the auspices of General Charles O’Hara,

At that time Governor of the Fortress;

Completed A. D. 1804,

Under those of the succeeding Governor,

His Royal Highness,

EDWARD,

Duke of Kent and Strathem, K. G.

General of His Majesty’s Forces, &c.,

The Garrison library building in Gunner’s Parade (1830 - Frederick Leeds Edridge) (See LINK)

A similar portrait taken a while later (1834 - Lieutenant H. A. West ) (See LINK)

In a show of gratitude the Library Committee decided to erect a bust of the Prime Minister in a specially incorporated niche in the front wall of the building. For unknown reasons the bust never materialised and the niche remains empty to this day.

In a very short space of time the library became what was essentially an officers’ club and membership was restricted accordingly. Apart from the library the premises also boasted a fives court. This game, with its Etonian connections, would have appealed to the officer class as many of them were public school boys. This part of town eventually came to be known as the Ball Alley, a name which was soon corrupted by the locals into el Balali. For less strenuous exercise the place also boasted a billiards room.

The 1837 Catalogue of Books of the library includes a list of subscribers. Among the various honorary members which include various consuls General Castaños who was the Spanish Governor of the Campo Area there one single local non-British name - that of Joseph Francia esq.

Joseph was the uncle of a very influential local businessman called Francis Francia. He was also a member of the Catholic Junta of Elders as well as having the honour of being the first local-born individual to become a barrister. But none of these attributes explains why he was accepted as a subscriber. There were plenty of other phenomenally rich and influential locals who should have been able to avoid being black-balled if they had applied for membership. The fact that they didn’t suggests that they knew that they would have been.

Joseph was the uncle of a very influential local businessman called Francis Francia. He was also a member of the Catholic Junta of Elders as well as having the honour of being the first local-born individual to become a barrister. But none of these attributes explains why he was accepted as a subscriber. There were plenty of other phenomenally rich and influential locals who should have been able to avoid being black-balled if they had applied for membership. The fact that they didn’t suggests that they knew that they would have been.

Garrison Library book catalogue which included an introduction to the history of the place and a list of subscribers (1837)

All in all it was a pleasant place for officers to spend a few languid or energetic hours in the company of people of their own class. Its fine gardens, atmospheric reading rooms and air of luxury made it a slightly exotic version of that uniquely English contribution to civilization; the gentlemen’s club.

During the very early 18th century people like Thomas Walsh (see LINK) who visited Gibraltar as a young captain of the British Army on his way to join Sir Eyre Coote’s military campaign in Egypt, enthused on the fact that the committee appointed to choose which books to buy, selected only ‘the very best publications’ and that every officer on his arrival was required to pay one week’s wages to the library’s funds. It meant that the library was always well attended and admirably supplied.

Plaza de los Cañoneros - Gunner’s Parade - with the Garrison Library on the right (1820 - Henry Sandham) (See LINK)

Officers’ wives were of course periodically invited to the dances and balls which were held there on various occasions – Ms Fyer must have been at the top of the invitation lists - but its exclusivity was its most treasured characteristic. In fact, according to John Galt in his Voyages and Travels, (see LINK) ‘the families of the local merchants were never admitted to the balls given by the military’. This . . . unpleasant line of separation’ had been ‘drawn, in consequence of the great number of low and vulgar mercantile adventurers who have settled in Gibraltar.

Galt, of course, only spent a few days on the Rock here and there and can hardly have had time to develop any profound insights into the nature of a local population that was continuing to grow. A census taken less than a year after his last visit revealed that there were well over eleven thousand civilians living on the Rock. They now outnumbered the military by a considerable margin.

Inside the Garrison Library - Gibraltar’s contribution to civilisation

By 1827 the novelty of the Garrison Library seems to have palled. According to Andrew Bigelow, (see LINK) the place was ‘little used, not even for the purpose of an occasional lounge.’ But then Bigelow was also of the opinion that ‘literary tastes and pursuits were quite foreign to the Rock.

Here and there a shelf may be found in the corner of some miscellaneous warehouse, where a few dictionaries, hornbooks, classical readers and copies of common prayer’ were kept but little else. Obviously warming to the theme he notes that ‘occasionally, a novel or the last poem, or a number of a review or magazine, straggles into the Garrison, but even these are scarcely noticed.

And yet as further proof that no two witnesses will ever come up with the same story, Thomas Hamilton (see LINK) who visited Gibraltar that same year was of the opinion that the Library was of a quality which few other Garrisons could boast. By 1837 R. Montgomery Martin in his British Colonial Libraries (see LINK) carries things one step further and insists that the "public library" founded by Colonel Drinkwater" had become "one of the finest in Europe."

Reading through the lines - or should I say “their lines” - one gets the impression that historians were generally of the opinion that as most of the residents could hardly read, libraries were viewed by them as simply yet another eccentric British bit of nonsense.

True, there is little historical evidence to suggest that the majority of the civilians felt any great sense of pique at being excluded from the Garrison library but this might have more to do with the almost complete indifference shown by many British historians - even the most modern ones - as to what any of the locals thought about anything.

In the 1830s Benjamin Disraeli (see LINK) came to visit he was told that it contained more than 12 000 volumes. He also found out that the library had a copy of his father’s Literary Characters, a book which he had edited himself.

Benjamin Disraeli (See LINK)

When he discovered that it was looked upon as a ‘masterpiece’ he ‘apologised and talked of youthful blunders; but finding them, to his astonishment, sincere, and fearing they were stupid enough, to adopt his ‘last opinion’, he shifted his position just in time.’ All of which says more about Disraeli’s overweening vanity than the intellectual shortcomings of the Garrison’s officers. From then on, however, the Library became one of the best known institutions on the Rock and not a visitor passed by without writing about it.

Josiah Conder also writing in the 1830s and on the whole rather indifferent to most things Gibraltarian - was of the opinion that the Garrison Library,

Josiah Conder also writing in the 1830s and on the whole rather indifferent to most things Gibraltarian - was of the opinion that the Garrison Library,

. . . together with the sensible and polite conversation of the engineer and artillery officers, most of whom are men of education and liberal minds, gives an agreeable tone to the society and manners’ of Gibraltar.

But perhaps the Library deserves one mid 19th century quote as it appears on Richard Ford’s Handbook for Travellers in Spain (See LINK) a work renowned for its venomous descriptions of most things Gibraltarian. Here in the Garrison Library,

. . . let the traveller with the sweet Bay and Africa before him, a view seldom rivalled, and never to be forgotten, look through the excellent Historia de Gibraltar by Ignacio Lopez de Ayala. (See LINK)

Richard Ford - Apparently he liked dressing up like a 'native' when he was travelling through Spain

Around the 1860s a “New Wing” was added to the Main building. One of the reasons given for this extension was the need for a Ladies Room. A few decades latter

View of the “New Wing” of the Garrison Library (1880 - The Graphic - Sketches at Gibraltar - detail)

Photographic views of the Library from the late mid to the late 19th century

Garrison Library book labels

By 1879, and according to the Gibraltar Directory of that date compiled by Major Gilbard, (see LINK) new facilities had been added to the Library:

An adjoining building, known as the Pavilion, has been attached to the library. It contains Reading and Billiard rooms, a Dressing-room and a small Bar.

The illustration captioned “View of the “New Wing” shown above, was taken from the Pavilion. Apparently some bright spark in the Library Committee came up with the idea of creating a separate club to be known as the Mediterranean Club. The idea was to protect the Library’s income by using the club for other types of activities - and rake in much needed extra money from a new set of subscribers.

The Med would be open to all subscribers of the Garrison Library and to Gentlemen residing at or visiting Gibraltar. The most important consequence, of all this, however, was that although the management and membership of the new club was separate from that of the Garrison Library, both sets of members were allowed to use each other’s facilities.

The above of course meant that the “Fundamental Laws” of the Garrison Library needed changing. The fact that it required no less than three official meetings over three years and the production of a report with recommendations by a special committee suggest that not everybody was enamoured with the idea of having to hob-knob in future with the great unwashed - however rich and influential they might be.

The Med would be open to all subscribers of the Garrison Library and to Gentlemen residing at or visiting Gibraltar. The most important consequence, of all this, however, was that although the management and membership of the new club was separate from that of the Garrison Library, both sets of members were allowed to use each other’s facilities.

The above of course meant that the “Fundamental Laws” of the Garrison Library needed changing. The fact that it required no less than three official meetings over three years and the production of a report with recommendations by a special committee suggest that not everybody was enamoured with the idea of having to hob-knob in future with the great unwashed - however rich and influential they might be.

Part of the 1897 report of the special committee

But old habits die hard and the Med was relatively short lived - the entire project was put to rest in the 1930s and the Garrison Library was again the preserve of the British Officers. The locals were once again excluded.

In 1897 Governor Robert Biddulph created a small local museum inside the Garrison Library - a complete waste of time in so far as the rest of the population was concerned in that of course the place was completely out of bounds to the vast majority of them.

In 1897 Governor Robert Biddulph created a small local museum inside the Garrison Library - a complete waste of time in so far as the rest of the population was concerned in that of course the place was completely out of bounds to the vast majority of them.

It would become the fore-runner of the present day Gibraltar museum but Biddulph’s original choice of venue shows the invariably dismissive not to say contemptuous attitude of a whole raft of our military Governors - almost throughout the 19th century and beyond - towards the civilian population.

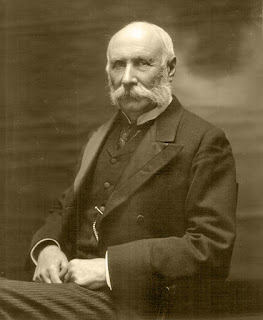

Sir Robert Biddulph (1906 - V and A Museum - Lafayette Archive)

Anachronistically and despite Gibraltar’s growing political muscle and the hand-over of much of the previously owned Ministry of Defence - and other military property - during the later part of the 20th century, the Garrison Library continued to be under the thumb of a trust made up mostly of officers who tenaciously resisted all efforts to democratise its membership so as to include the locals on a level pegging.

In September 2011, however, the Trust gave in, and the Library was finally handed over to the Government of Gibraltar. I left the Rock in 1961 and I am sad to say that I have never set foot inside the place. I have always regretted it. I would have been able to improve most of my articles on the social history of my home town had I been able to make use of the Libraries magnificent local historical resources.

But to be honest perhaps what I mostly regret is that such an exclusive institution as the Garrison Library should have been allowed to exist for so many years and right up to the 20th century. Perhaps more generally it is downright embarrassing to be reminded by the Colonial Office List of 1867 that every single colony of the British Empire had some sort of officially recognised body to represent the local inhabitants except for the Kaffrarians . . . . . and the Gibraltarians.